The economy of England, if not the largest, was probably the most advanced and complex in Europe. Still strongly based upon the cloth trade, still with a predominantly agricultural base, it showed aspects of developing industrialisation in shipyards, cannon-foundries, brickworks and ironworks. The range of trades was great. The developing skills in medicine and surgery required new and specialist instruments. New imports were coming in from west and east, including tobacco (against the use of which the new king wrote a book) and chocolate. To control and protect trading in far-off places, new businesses had been created, the Muscovy Company and the Levant Company, respectively granted monopolies on trade with Russia and the eastern Mediterranean. The regulation of this diverse activity had become the joint concern of the Council and of parliament, with some men being members of both bodies, as Sir Francis Walsingham had been. The prime function of parliament remained 'supply', the granting and securing of the royal finances.

James's policy of peaceful relations with Spain, though opposed by diehards, was a sensible one and brought dividends in trade. Salisbury's death in 1612 removed his most efficient and respected counsellor; from then on James was excessively influenced by his own court favourites. Between 1614 and 1621 he did not summon parliament at all.

TROUBLE FROM ABROAD

Despite a continuing alliance with England, Dutch merchant venturers established colonies and trading stations and organised themselves to keep English traders out. Dutch fishermen considered the North Sea their own and fought off English vessels. Having made peace with Spain, and aware that France had no fleet, the English government allowed the navy to run down, and while its merchant fleet grew, England was no longer capable of enforcing control even of its own coastline. Despite these difficulties, English colonies were successfully established in Virginia (where Jamestown became the first permanent English settlement in 1607), Bermuda and Barbados. From 1620, the private enterprise of non-conforming Puritans established the New England colonies. Acceptance of the Bohemian crown by a German prince, the Elector Palatine, who was married to James's daughter Elizabeth, widened the war until, from the extreme ends of Europe, Spanish and Swedish armies fought across German principalities and Austrian duchies, assisted by hosts of mercenaries from England, Scotland and Ireland. England played a peripheral part in this great struggle.

CHARLES I: RELIGIOUS DIVISIONS AND CONFLICT

WITH PARLIAMENT

Buckingham when James I died in February 1625, King Charles I maintained the favourite as chief minister. There were many reasons for Buckingham to have opponents and enemies. He was a social upstart, he was a corrupt counsellor who sold official posts and peerages, he encouraged the king's hostility to parliament, and he was an incompetent politician and an inept general. Almost his only useful contribution was, as Lord High Admiral, to develop the use of frigates for the royal navy.

The great Seal of Charles I Charles I

Buckingham's continued role played a large part in parliament's reserved attitude to Charles I at the start of his kingship: instead of granting the king ‘tunnage and poundage’ (the proceeds of import and export duties) for life, or an extended period, it gave him only one year. War had been declared on Spain in 1624, and Charles extended hostilities to France in 1626. Such campaigns as there were, including an attempt to replicate Drake's old success at Cadiz, and an expedition led by Buckingham against the lie de Re in France, were failures. Buckingham, defended by the king against parliamentary impeachment, was assassinated by a disgruntled officer in 1628.

SCOTLAND REVOLTS

The unravelling of Charles I's royal autocracy began in an unexpected place. Charles mustered an army to restore the Scots to discipline. The Scots mustered an army that was altogether more formidable than the ill-trained royal levies, and a peace was patched up, though it was plainly not going to last. The Scottish army, encamped in the north and subsidised at £850 a day, was the guarantor that the parliament would not be dissolved by royal order. Names that would soon ring out on battlefields participated in its work, including the quiet but influential member for Huntingdon, Oliver Cromwell.

PARLIAMENT GAINS THE UPPER HAND

In October 1641, news of a rebellion in Ireland, under Catholic leadership, brought anti-Catholic feeling to new heights, whipped on by hysterical speeches and propaganda. This artificial climate of suspicion and tension endured into 1642, while attitudes hardened both on the religious and political issues. Perhaps in anticipation of attempts to impeach the queen, Charles's attorney-general impeached five members of the Commons and one peer, and on 4 January, with a large force of soldiers, the king came himself to the House of Commons to arrest them. Forewarned, they had taken refuge in London, which became almost on the instant an openly insurgent city The king left for the north, where he would still find loyal support.

In April he was refused entry to the city of Hull, where an arsenal of weapons was stored. Opposing authorities were now publicly asserted. Parliament set about raising a militia. Bу July, opposing bands of royalist and parliamentary supporters were already fighting. On 20 August, at Nottingham, the king raised his standard and called on all who supported him to join the ranks. With both sides protesting that they were defending England's ancient rights, laws and customs, the Civil Wars began.

THE CIVIL WARS

Beginning as a constitutional war, exacerbated by religious dispute, its ending was dominated by struggles between different religious factions. At the start, the royalists' great asset was the king himself. He was still king of the whole nation and could command a strong traditional loyalty across the population. The royalist troops based in Oxford gained an ugly reputation for looting. Most of the nobility rallied to the king, and he had strong support in the West Country and the north. From his headquarters at Oxford, Charles still commanded a great swathe of the country. A 'self-denying ordinance' forbade members of parliament also to be commanders in the field. By irresistible demand from the ranks of the army, one exception was made to this: the Lieutenant General of Cavalry, Oliver Cromwell. Parliament's 'new model' army, with Fairfax as general and Cromwell as his deputy, was paid, trained, disciplined, and instilled, from its leaders down, with a will to win. 'Ironsides' was Rupert's nickname for Cromwell; it soon spread to his troopers. On 14 June 1645, with Charles I leading his troops, the royal army suffered a decisive defeat at Naseby. A push to the west followed and the royalists of Cornwall surrendered in March 1646. As the parliamentary forces set about besieging Oxford, the king slipped out and in April gave himself up to the Scottish army which was encamped at Newark.

PARLIAMENT DIVIDED: THE ARMY GAINS CONTROL

This brought about an end to hostilities and a whole new set of uncertainties. Charles had surrendered his person but not his cause. For nine months the Scots held him while negotiations went on. The Scots wanted to see the Solemn League and Covenant implemented. When it was finally plain that Charles would never agree to this, they washed their hands of him. Prominent campaigners for the king were heavily fined and frequently forced to sell off their land to friends of parliament. A great mass of the middle ground population were angered by the suppression of Anglican worship, the forbidding of the Prayer Book, and the ousting of some two thousand parish clergy. The Independents were enraged by such measures as life imprisonment for Baptists, and the prohibition of laymen from preaching. These issues were brought to climax by an ordinance for disbandment of the army, apart from a few regiments retained to subdue Ireland. The war was won, and the cost of a standing army was very great; there were growing complaints about the level of taxation required. But the soldiers' pay was in arrears, and the new model army was imbued with the spirit of the Independents. The army refused to stand down, and at its head, looming larger than Fairfax, his nominal superior, was Oliver Cromwell, now the most powerful man in England.

Cromwell, backed by his able son-in-law, Henry Ireton, took possession of the king and brought the army to London. By August, Fairfax and Cromwell's regulars had smashed the royalists. The army was now in indisputable control of the country. When the Long Parliament met again on 6 December 1648, Colonel Thomas Pride seized 137 members, all Presbyterians, placing 41 under arrest. Sixty Independents now formed the House of Commons, a 'Rump' even less representative of the country than the previous assembly It proceeded to take momentous decisions, passing a bill to arrange the trial of the king, and voting that 'to levy war against the Parliament and realm of England was treason'. A special High Court was convened to try the king. No judge would sit in it, and Fairfax would have none of it, but Cromwell, backed by the army, pressed on. Denying the legitimacy of the proceedings, Charles refused to plead. He was found guilty, sentenced to death, and beheaded in front of a great, silent crowd in Whitehall on 30 January 1649.

Oliver Cromwell

ENGLAND LOSES A KING – AND BECOMES

A COMMONWEALTH

England was proclaimed to be a 'Commonwealth', under the government of the House of Commons and a Council of State, with Cromwell as its chairman. The House of Lords was abolished.

Such events encouraged the extreme democrats among the army rank and file, 'Levellers' and 'Diggers' who demanded annual parliaments and social equality, but their disjointed attempt at a coup was forcibly put down by Cromwell, who did not share these aspirations. Ireland, still in a state of revolt, and Scotland, which had proclaimed Charles II as its king, were to be incorporated into the Commonwealth, which claimed all the dominions of the executed king. Cromwell took an army to Ireland and commenced the subjection of the country, which Ire ton completed in 1650. Cromwell meanwhile turned on the Scots, but in 1651 the Scots brought war into England, when Charles II accompanied an invading army. The hope was to arouse English support, but little was forthcoming, and Cromwell defeated them at Worcester on 3 September 1651. Charles II fled abroad. With the 'crowning mercy' of Worcester, the Civil Wars were ended, and England faced a new era.

The lowest point of English estimation of Oliver Cromwell came at the restoration of the kingdom in 1660, when his decayed corpse was exhumed, dismembered and abused. His old admirers kept their heads down. The highest point was when he was offered the crown, in 1656. But the stock of the great king-slayer has generally been high, in a deeply monarchic country. This is partly owed to his personal qualities of honesty and sincerity, but mostly to the fact that his rule was successful. The Commonwealth was born in the immediate aftermath of shock, large-scale bloodshed and bitter division. Civil war, disrupted trade and bad harvests had made the late 1640s a grim time. When Cromwell died, his state had unified England, Wales and Scotland as a single entity, was united, prosperous, at peace, and had made itself respected abroad. At first his energies were absorbed in the subjection of Ireland and Scotland. In Ireland, where, in sacking Drogheda and Wexford, he permitted his troops to run amuck in a way he never did in Great Britain, he earned loathing. From January 1649, England was under the control of the 'Rump Parliament', watched over with increasing irritation and impatience by the army. The Rump's main object seemed to be its own preservation, and in this it was aided by the military leaders, whose principles demanded a general election and a new representative parliament, but who shrank from the prospect of the Anglican-royalist dominated assembly that was likely to result. On 20 April 1653, Cromwell took matters into his own hands. After a few blunt home-truths – 'Do you think to sit here till Doomsday come?' quoted a balladist – he brought a troop of soldiers into parliament, dissolved the Rump and sent the members home. From then on, though he attempted various forms of quasi-parliamentary government, his own presence at the head of affairs was the consistent and driving element in national life. The 'Barebone's parliament', composed of nominated members, one of whom, Praise-God Barbon, gave it its name, had a brief life in 1653.

In December of that year Cromwell assumed the title of Lord Protector. In September 1654 the first all-British parliament met, with English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish members; by Cromwell's own constitutional document, the Instrument of Government, he could not dissolve it for five months, but he did not wait a day longer. Its offence was to discuss the lord protector's role, rather than to govern as he wished it to. For eighteen months he ruled on his own, then in late 1655 he divided England into twelve military districts, each governed by a major-general with wide powers. This reminder that the army-paid for by substantial and efficiently collected taxes – was still in command caused widespread protest. Still experimenting, Cromwell called a third parliament in September 1656; by now his experience had taught him that only a partial reversion to traditional forms would bring long-term stability, and he planned a new Upper House. It was this parliament that offered him the crown. Though he refused it, in the knowledge that acceptance would split the army and bring more strife, the protectorship in its last phase was hardly distinguishable from a monarchy; it was even made hereditary.

The Great Seal of the Commonwealth The Great Seal of the Commonwealth: reverse

ENGLAND UNDER THE COMMONWEALTH

A famous later comment by Lord Macaulay said that the Puritans abolished bear-baiting, not because it gave pain to the bears, but because it gave pleasure to the spectators. With varying degrees of success, Cromwell's administration sought to curb the 'sinful' pleasures of old England, from maypole dancing to madrigal singing. It was easy enough to close a theatre: much more difficult to stop traditional seasonal fun and games in every village, vestiges of paganism though they might be.

But the Commonwealth allowed a wider range of religious practice than previous governments. The official religion of the state was severely Puritan. Everyone paid tithes to this nameless church, which occupied the place of Anglican Christianity without its liturgy. But no one was compelled to attend, or to swear to its tenets. Provided it was done discreetly, Anglicans, Anabaptists, even Catholics, were able to worship according to their own rituals or lack of them. Cromwell, who had stabled his horses and billeted troopers in some of the country's great cathedrals, had a wide tolerance of religious expression as long as it stayed outside of politics. During his rule, Jews were admitted to England for the first time since Edward I had expelled them in 1290; their arrival, along with the continuing inflow of Huguenots, played its part in the accelerating growth of London as the world's greatest trading city, overtaking Amsterdam.

The Commonwealth was an expensive state to administer. There had never been a standing army before; now it was 50,000 strong. The strength and size of the navy were also greatly increased. These were costs on top of the normal costs of government. But wealth was increasing. The restoration of peace encouraged the resumption of trade and manufacture. Evidence of this wealth can be seen in the foundation and enlargement of schools and the building of almshouses and hospitals. London, the seaport towns, the cloth towns, the mining and manufacturing districts (still small but densely populated) had always backed the parliamentary cause, and the rewards of peace were theirs to work for. Whatever else the Protectorate prohibited, it did not prohibit trade, enterprise, profit or education. Economic strength extended outwards. The Rump had begun a war against the Dutch in 1652, a new stage in the established struggle over control of the North Sea, of dominance in sea-trading, and in the establishment of colonies. Parliament and then the Commonwealth found an admiral in Robert Blake to rival the great Dutchman, Van Tromp. In 1649 Blake destroyed the fleet created by Prince Rupert and in doing so brought English naval power into the Mediterranean. Defeated by Van Tromp off Dungeness in 1652, he won a victory off Portland in 1654, and in a further victory off Texel, won by another general-at-sea, George Monck, Van Tromp was killed.

By 1654, the revitalised navy had established the position of mastery in the narrow seas which it was very rarely to lose again. When Cromwell made peace with Holland in 1654, Dutch concessions benefited English trade. In 1655 war was declared on Spain, and an English naval expedition captured Jamaica but failed to take Hispaniola, its prime objective. At Tenerife, Blake destroyed the Spanish fleet in April 1657. In the Commonwealth's dual foreign policy of protection and extension of English trade, and Cromwell's ambition to form a Protestant League, it was on the whole English interests that won. A treaty with France – where the Edict of Nantes still extended toleration to Protestantism – and joint attacks on the remaining Spanish holdings in the Low Countries, won the possession of Dunkirk. The Commonwealth, whose first envoys had been insulted and even murdered with impunity in European capitals, had made itself into a significant force in world affairs.

THE RESTORATION OF THE MONARCHY

The death of the Protector, in his fifty-ninth year, threw all his achievement into disarray. His son Richard, aged thirty-eight, named as his successor, was well-intentioned but not of his father's calibre, and had not grown up with the training, expectations and advice of an heir-apparent. Nor could he command the historic obedience given to a king.

The Great Seal of Richard Cromwell Richard Cromwell

At first he was backed by the army, but soon it was plain that the army commanders had conflicting views about the way forward. People who supported, or were working for, the accession of Charles II were pleased to see the army begin to disintegrate into factions, some supporting a return to the republican ideals of 1649, some looking for a generalissimo-figure to assume control. The parliament called by Richard was equally riven by contrary opinions, with many royalist sympathisers. He dissolved it in April 1659 and resigned his post, retiring to obscure country life. Casting about with a degree of desperation for a national authority with some claim to legitimacy, a military committee recalled the surviving members of the Rump Parliament so ignominiously dismissed by Oliver Cromwell. Forty duly appeared, to be blown hither and thither in their discussions by pressure from different generals, until one of the two most determined soldiers, John Lambert, forced its dissolution. While royalist demonstrations and local risings became more frequent, the other soldier, George Monck, commanding in Scotland, crossed into England with his army. Already in communication with Charles II and his advisers, he destroyed Lambert's efforts to resist his advance, and took control of London. Here he summoned, not the residue of the Rump again, but all the surviving members of the Long Parliament, as it was before Pride's purge. Monck was now in open negotiation with the exiled court at Brussels, but it was in the end this 'Convention Parliament' which, in May 1660, formally invited Charles, Prince of Wales and already King of Scotland, to assume his father's English crown.

18TH AND 19TH CENTURY BRITAIN

(Development of political institutions.

The America War of Independence. Conquest in India.

The beginning of industrial revolution. Luddites.).

19th century Britain.

(The growth of the British Empire.

Colonies and colonial Trade. The Bank of England.

The industrial revolution. The 1832 Reform Bill.

The Charter and Chartism. The Victorian Age. The emergence of Trade Unions and Co-operative Societies. The post office.

The Education Acts of 1870, 1880, 1891.).

WAR WITH THE AMERICAN COLONISTS

Though North is inevitably associated with the loss of the American colonies, their alienation had begun earlier. Some of the colonies, like Massachusetts, had been founded by men and women who had felt forced to leave England and their descendants had not forgotten the fact. Pennsylvania had been а ‘hо1у experiment' in social and religious freedom. The spirit of the colonists did not fit well with the attitudes of the governors and military men sent out from England for short terms of office. In 1766, at Pitt's urging the stamp tax had been repealed, but Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the last cabinet before North's, applied taxes to American imports of lead, paper, glass, painters' colours and tea, causing furious protest. North repealed all these, except the tax on tea. This was not enough to placate the colonists, especially as the duty was kept not for the revenue it generated but to maintain the principle that parliament could tax the colonies. In 1773 the East India Company was in financial trouble, which the government tried to resolve by giving it the monopoly on tea supply to America. This offended the American merchants and led to smuggling and Company ships being turned back, and to the celebrated Boston Tea Party, when colonists disguised as Indians threw part of a cargo into Boston Harbour. Heavy-handed British action to obtain compensation from Massachusetts, and then to annul its constitution, led to the Continental Congress of September 1755: the colonies found unity in opposition, and British attempts to divide them failed. Fighting began on 19 April 1775, at Lexington, though the American Declaration of Independence was not made until 4 July 1776.

This was a war quite different to any later colonial wars. English principles, English pronouncements, and the words of English philosophers like John Locke, were turned against the London government and its apologists by the rebel colonists. But the war was not waged in any apologetic spirit by the British, and majority public opinion in England was firmly on the government side, with only those of strong radical sympathies against it. The final 'olive branch petition' from the Congress was ignored, and an army of 20,000 men was mustered. Many were German mercenaries from Hesse and Hanover. Whilst the British armies could win battles, they were not equipped to deal with a mobile enemy spread across a vast countryside, nor, after victory, to hold down a hostile, well-organized and resourceful population. In October 1777 General Burgoyne, with an over-extended army, surrendered at Saratoga. Soon after this news was known, France, under Louis XVI, recognized American independence and declared war on Great Britain. Just before his death, in 1778, Chatham made his last speech in parliament, urging the House of Lords to make a reconciliation with America, but the king's policy was to fight on all fronts, and North was his obedient servant. By 1780 Spain had also declared war, and war was declared against Holland, which refused to allow its merchant ships to be searched for American supplies. Russia and the Scandinavian countries adopted a posture of 'armed neutrality' for the same reason. Britain was again involved in international conflict. Colonial empires, and control of the vital sea-routes, were still the great prizes, and the French fleet had been re-established as a formidable force.

Treaty of Versailles ends War of American Independence with British acceptance of American colonies’ independence.

The national debt was around £860 million in 1816; in The Common People G.D.H. Cole and Raymond Postgate reckoned that 'each citizen of the country owed his fellow-citizens nearly £45' - this was at a time when agricultural wages were falling from a wartime high of sixteen shillings a week to a level of eight or nine shillings, less than £24 a year. On this basis the involuntary 'debt' was more than two years' wages. And, as these authors point out, it was chiefly from the poor that the government was to claim the funds. Income tax, which, although widely dodged, was collected from the wealthier citizens, was abolished immediately after the war's end.

The government needed to raise £31,500,000 each year simply to pay interest on the national debt. Tea, sugar, beer, soap and candles were all heavily taxed. Another important concern was corn prices. The prices of most commodities fell after the war. But in 1815, at the urging of the strong farming interests represented in parliament, a Corn Law was passed, forbidding the import of corn unless the price rose above £4 a quarter (or £3 10s. in the case of wheat from Canada). The result of this was to keep the price of bread artificially high at a time of plummeting wages and high unemployment.

A further issue for the government was law and order. Over three hundred thousand men returned from the army to civilian life to find that a slump in demand both at home and abroad had drastically reduced industrial production. There were few jobs to be found, and wages were very low. Factory owners preferred to employ women and children, who were cheaper and more controllable. The government did not see unemployment as a matter for its attention, but it was concerned about the unemployed as a source of public disturbance. There was already industrial trouble for another reason. The invention of the power loom had placed the thousands of cottage-based hand-loom weavers at an increasingly severe disadvantage. Factory production did not monopolise the industry but left a varying, marginal amount of work for the hand-loom weavers. In a period of slump, this meant destitution for the weaving households, whose numbers had greatly increased through immigration from Ireland. Competition for work in a declining market led to a breakdown in the traditional system of apprentice and journeyman. From 1811 the 'Luddite' movement arose in Cheshire, Lancashire, Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire. It was not a campaign against new machinery as such, at least not in its initial stage: the machines of employers who broke the rules were smashed. The machine breakers, supposedly led by the elusive 'Ned Ludd', appeared to be well organized and had the passive support of their fellow-workers.

Restoration of the gold standard, in 1819, was the main element in economic policy, and, like most aspects of the Liverpool government's thinking, it betrayed a yearning for the old days before 1792, when Pitt had presided over a prosperous and peaceful country. Like all such nostalgic views, it omitted any sight of the problems that Pitt had ignored or failed to resolve, almost all of which, in a more modern guise, remained, and now demanded action. From 1820, as economic recovery gradually began, and the panic sense of an imminent revolt decreased, the government began taking some account of these.

A STRONG AND PROUD NATION

During the reign of Queen Anne, from 1702 to 1714, particularly its early years, acceptance of the new system was encouraged by a sharp rise in England's international prestige. A series of victories by English-Dutch armies under the command of Marlborough (made a duke by his old patroness) at Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde and Malplaquet between 1704 and 1709, showed that the balance of power in Europe had changed. Pride and gratitude were reflected in the gifts bestowed on the duke, including the building of a huge and opulent mansion, Blenheim Palace.

Fire-ravaged London was being rebuilt under the supervision of Sir Christopher Wren, and a new and vast St Paul's was rising above the Thames, with an Anglican dome whose scale surpassed that of Michelangelo's St Peter's in Rome.

In natural philosophy Newton had made England supreme. Fire and water had been harnessed in a new way, and from 1698, Thomas Savery's atmospheric steam engines, improved by Thomas Newcomen in 1705 and 1711, marked the opening of a new industrial age. It was a self-confident society, more mature than that of the Restoration, and more united.

The Atlantic had ceased to be a vast unknown and had become a network of trading routes to a string of colonial ports from Nova Scotia to the West Indies. In addition to the exchange of manufactured goods for the products of the New World, a new and lucrative business was growing fast in the acquisition of black African tribespeople and their transportation and

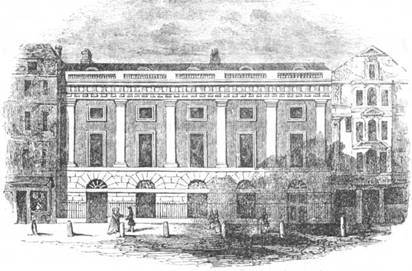

East India House, London, 1726

sale as slaves on the sugar plantations. The East India Company, its charter going back to 1600, was re-established and enlarged in 1708; its fleet of heavily armed merchant ships was a navy in itself.

With so much money in the country, and the government's need to borrow vast amounts to pay for the war, new ways of running the nation's economy were found. The Bank of England was established with government backing in 1694 by William Paterson, a Scot.

A few independent institutions were established to support and exploit the new developments. From 1692, Edward Lloyd's coffee house in the city of London had been a centre for ship-broking and marine insurance, and he had started a commercial journal of record, Lloyd's News. From 1726 this was reestablished as Lloyd's Lists, and Lloyd's Register of Shipping was begun at the same time. For over two hundred years, until the organisation's downfall and reform in the 1990s, Lloyd's underwriters would make large annual profits from an ever-enlarging insurance business in which shipping became merely a part. The Bank of England had a monopoly of all business operations that used the joint-stock principle - the South Sea Bubble was not forgotten – but the Stock Exchange began business in 1773, and local banks, like that begun by the ironware-making Sampson Lloyd in Birmingham in 1765, helped to finance expansion, many of them going bust in the process.

LATE SUMMER, BANK HOLIDAY

On Bank Holiday the townsfolk usually flock into the country and to the coast. If the weather is fine many families take a picnic-lunch or tea with them and enjoy their meal in the open. Seaside towns near London, such as Southend, are invaded by thousands of trippers who come in cars and coaches, trains, motor cycles and bicycles. Great amusement parks like Southend Kursaal do a roaring trade with their scenic railways, shooting galleries, water-shoots, Crazy Houses, Hunted Houses and so on. Trippers will wear comic paper hats with slogans such as "Kiss Me Quick", and they will eat and drink the weirdest mixture of stuff you can imagine, sea food like-cockles, mussels, whelks, shrimps and fried fish and chips, candy floss, beer, tea, soft drinks, everything you can imagine.

Bank Holiday is also an occasion for big sports meetings at places like the White City Stadium, mainly all kinds of athletics. There are also horse race meetings all over the country, and most traditional of all, there are large fairs with swings, roundabouts, coconut shies, a Punch and Judy show, hoop-la stalls and every kind of side-show including, in recent years, bingo. These fairs are pitched on open spaces of common land, and the most famous of them is the huge one on Hampstead Heath near London. It is at Hampstead Heath you will see the Pearly Kings, those Cockney costers (street traders), who wear suits or frocks with thousands of tiny pearl buttons stitched all over them, also over their caps and hats, in case of their Queens. They hold horse and cart parades in which prizes are given for the smartest turn out. Horses and carts are gaily decorated. Many Londoners will visit Whipsnade Zoo. There is also much boating activity on the Thames, regattas at Henley and on other rivers, and the English climate being what it is, it invariably rains.

VICTORIAN ENGLAND

THE CLASS STRUCTURE

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate;

God made them, high or lowly,

And ordered their estate.

These lines, now usually omitted, from the popular children's hymn 'All Things Bright and Beautiful' were penned in 1848 by Cecil Frances Alexander, wife of the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin. They serve to show that inequalities and social gulfs not merely existed but were taken for granted as part of the established scheme of things, at least by those on the comfortable side of the gate. In fact social mobility was much greater than such lines suggest. The old resilience in English society, which could be seen in much earlier times, was still there in the nineteenth century. A commoner, even someone born in poverty, could make his way by talent and good luck to the peak of society. Benjamin Disraeli was a prime example. Where once the church had been the means of ascent, now politics, commerce and industry all made occupancy of the castle possible to those who started with few material advantages. The success of the English upper class was in its absorption of such individuals. They assumed its habits, styles and attitudes, and if in the first generation they might be regarded as 'new money' and social upstarts, their children would blend in, by marriage and association, to maintain the social order. This was common ground between Whigs and Tories in politics; if the Whiggish interest tended to come from industry and trade, and the Tory interest from land, there was still a great deal of overlap between the two.

One of the consequences of the Reform Act was the consolidation of England's class structure. A simple breakdown into aristocracy, upper class, middle class and working class does not tackle the complex ordering of the social hierarchy. Its most numerous group was of course that of the workers, becoming ever more numerous as the population was on its way to doubling by mid-century, to double again by 1900. But the working class had its own strata and demarcations, of skilled labour and unskilled, of foremen and journeymen; of house owners and renters, of those in fixed employment and itinerants who sought seasonal work. Workers comprised men, women and children over theage of ten, and the greatest number were at the bottom end of the wage scale. Even if male and over twenty-one, they had no vote: the Reform Act's provision was that an elector must be a 'Ten Pound Householder' in a borough, and a 'Forty Shilling Freeholder' in the country constituencies. Hardly anyone of the working class could fit that requirement; indeed, to do so would place him in the lower reaches of the next socio-economic group. The lowest stratum of those actually working was found in the countryside, among the rural labourers, where a steadily dropping demand for workers – 18 per cent of the working population in 1851, down to 11 per cent by 1871 – helped to keep wage levels low. Until the 1870s these were also among the least organised of any working-class group, with no trade union and no bargaining power to increase their wages or improve their often scandalously bad housing. Picturesque enough from the outside, the countryman's cottage, in the various regional building styles which existed prior to the mass-producing industrial brickworks, was dark, damp and insanitary inside. In towns and cities, the unskilled workers were the lowest-paid. If they were male, they had some hopes of progressing towards the more skilled and better-paid trades, but for women workers there was scant chance of this. They remained as basic machine-minders. These groups also had little negotiating power. With no special skills to offer, they were easily replaceable, especially as the continuing drift of population from agricultural counties like Norfolk and Lincoln into the cities created a permanent supply of fresh labour. Skilled workers – miners, ironworkers, bricklayers, riveters, carpenters, engine-men, plasterers, glaziers and a host of other trades, some very recent – were in a stronger position to claim and hold out for higher wage scales.

WORK, TRADES AND PROFESSIONS

For the working class, a range of new work opportunities arose. Between the censuses of 1851 and 1871, the number of persons employed in domestic service increased from 900,000 to 1,500,000. This in turn reflected another important change, the rise of the professional 'middle' class. In the same period, the number of professional workers rose from 272,000 to 684,000 and continued to rise steadily. These were the teachers, ministers, engineers, industrial designers, accountants, lawyers, borough and county officials, army and navy officers, clerks, factory managers – a largely urban group, living in bigger terraced houses or separate 'villas', and employing at the very least a cook and a parlour-maid.

THE EDUCATION GAP

Within this great burgeoning of population, industry, activity and national wealth, there was a hidden flaw. England, which had produced the steam engine and Brunei's iron ship, and which had nurtured the intellectual explosions caused by the science of geology and – in 1859 – of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, the England that was among the most literate countries in the world, was falling behind in a crucial field. Education was not something that government considered to be among its responsibilities. It was not in the English tradition for a government to compel parents to send their children to school, or to set standards of attainment either in the old subjects or the new ones. While more centralized regimes in Europe and Russia established technical universities and national qualification systems, the English way was to allow things to happen through a mixture of individual initiatives and the gradually evolving practices of different crafts. This remains the case in medicine even today Engineers in England began as apprentices, either 'premium' ones whose fathers paid for them to enter the business, or ordinary apprentices who were paid a tiny amount. They learned on the shop floor. The Institution of Civil Engineers, founded in 1818, and that of Mechanical Engineers, in 1848, did not at first set out national standards. The universities, old and new, were more concerned with the humanities, law and divinity than with the sciences and technology, unlike those of the United States, where professors taught commerce, science and technology. In the later decades of the nineteenth century, it was increasingly evident that England was ceasing to be the prime nursery of new technology. If inspiration and application were what got the 'Industrial Revolution' going, technical education was vital in order to maintain it. But technical education in England lagged behind that of other industrialised countries, and as a result the engineer and technician never gained the social respect accorded to doctors and lawyers.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

THE CHARTIST MOVEMENT

AND THE ANTI-CORN LAW LEAGUE

In 1837, the leaders of radical groups in London combined to draw up a list of six points which they considered essential to the political and social health of the nation, and framed them in a petition to the House of Commons. They were: a vote for every adult male; electoral districts of equal size; a secret ballot in elections; annual parliaments; salaries for members of parliament; and abolition of the requirement for any MP to be a property owner. Five of these eventually became law and are seen as basic aspects of modern democracy; and most people will feel grateful to be spared an annual parliamentary election. In 1837, however, they met entrenched and indignant opposition. In 1838 the six points were formed into‘the People's Charter', and the Chartist movement received its name. Hundreds of local Chartist groups were formed, and hopes were high for a time. As in 1819, a Whig government set out to clamp down, using every means at its disposal, including infiltrators and paid informants. Chartism comprised a great number of disparate interest groups, all of whom subscribed to the six principles but whose further agendas, and methods of achieving them, ranged from the wholly legal to violence and assassination. The popular strength of Chartism is seen in the fact that the original petition, when presented in its massive entirety to parliament in 1839, was signed by 3,317,702 persons. The original leaders were overshadowed by a fiery orator from Ireland, Feargus O'Connor, who was neither an organiser nor a conspirator, and while Chartism remained a prime aspiration among the radical-minded, the heady hopes of 1838 were blown away by the abortive affray at Newport, Monmouthshire, anticipated and stamped out by the authorities in 1839. After that, despite strikes and demonstrations in different English cities, Chartism was wrecked. A second petition was rejected by parliament in 1842 and strikes in Staffordshire and Lancashire led to riots and disorder. While hardship bit deeply into the lives of the English, the government formed by Peel itself resigned – on the young Queen Victoria's refusal to admit some grand Tory dames to the exclusive, influential and wholly Whig circle of Women of the Bedchamber. For two years Melbourne returned to lead a doddering ministry that could not cope with Chartist and anti-Corn Law protest. The Anti-Corn Law League had grown very quickly from its foundation in 1838. Although cheaper corn prices were its great proclaimed aim, in fact it was a free trade movement supported by manufacturing interests, chiefly the cotton makers of Lancashire. Its leaders, John Bright and Richard Cobden, both emerged from the factory owners, and their 'liberal' radicalism which encompassed free trade had little to do with the popular radicalism of the Chartists.

The backers of the League had little interest in industrial reform; the freedom they wanted was manufacturers' freedom from government controls and tariffs. It has been described as the first important middle-class movement in politics, though its impact was largely confined to the textile-producing districts in the north, and it was identified in particular with the city of Manchester. In 1841 a general election returned Peel and the Conservatives with a majority of ninety.

The 'May 2nd Fenny Black' - the first known

posting of any stamp in the world

THE PENNY POST

As the scale of commerce between companies grew in the 1830s, and with the population becoming both larger and more mobile, the need for a proper postal system became pressing. Post had been not only very expensive, but paid for by the recipient. The privilege granted to MPs, of sending their mail free, was widely abused on behalf of their friends. This was just the kind of problem for a utilitarian solution, and a utilitarian was ready, in the person of Rowland Hill (1795-1879), a Kidderminster-born educationist with a keen interest in inventions and current affairs, and a member of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. From 1835 he conceived and promoted the idea of a national flat-rate postage charge, of one penny, using adhesive stamps, and his Post-office Reform was published in 1837. The technology was available; the railways were offering a rapid transport system; his problem was to convince the Post Office. In 1840, the flat-rate penny post was introduced. From 1846 to 1864, Hill was secretary first to the Postmaster General, then to the Post Office, and initiated further innovations, including parcel post, to provide Victorian Britain with the most efficient postal service in the world.

EDUCATION FOR ALL

One aspect of community life which the churches did control, or heavily influence, was education. Once a prime purpose of education had been to produce priests, and virtually all schools above the level of the dame-school teaching basic literacy were run by clergymen, whether Anglican or Dissenting. Religious education naturally was a large element in the curriculum. From Tudor times the sons of the upper classes had been sent away to school – a privilege they shared with the more fortunate orphans who were brought up in charitable foundations. These schools were notorious for brutality and bullying, and a process of gradual and uneven reform began under Thomas Arnold at Rugby School in 1828: the ethos of self-reliance, team spirit, competitiveness, sportsmanship, responsibility and conformity would influence other schools and certain national institutions, especially the army. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge were open only to committed male Anglicans; all their teachers had taken holy orders. Non-conformists wishing to educate their sons beyond grammar school level still sent them to Dissenting academies, where they were well taught but could not receive university degrees, or to one of the four Scottish universities.

Partly through fear of stirring up religious controversy, of stepping into church preserves, and spending money, the government avoided the matter of national education as much as possible until 1869. But from 1833 grants had been paid from central funds to help maintain church schools, at first only £20,000 a year, but by 1860 it was closer to £1 million. In the 1860s, such children as went to school normally left it at the age of eleven, to begin work. Two million children under eleven, it was estimated, were receiving no education at all. England was lagging far behind other countries in this respect. The United States and Prussia, with universal education, were seen to be moving into leading positions in the industrial and technological fields. France, Austria and Russia had much better technical education facilities. To institute a state education service in England was almost a revolutionary move, but from the radical section of the community there was an insistent demand; and even conservative Liberals like Robert Lowe, resistant to further political reform, could see the need. The Education Act of 1870 brought the state into education, though further acts would complete the process and universal free elementary education was only established in 1891. School boards were set up, with authority to compel attendance. The resultant great increase in the number of schools was significant in providing, for the first time, a large number of jobs for educated women. School education for girls led to the demand for higher education also, and the universities with varying degrees of reluctance – far greater among the old ones than the new ones - gradually opened their doors to female undergraduates. The faculties of medicine, law, and, of course, divinity, were the last bastions to fall.

THE FRANCHISE AND THE TRADE UNIONS

By 1885, all adult men had the vote and the country was organized into single-member constituencies. In 1888, elected county councils replaced the former system of management by justices of the peace and local boards. In 1891, elementary education was made completely free. Though the secondary education system remained largely voluntary and paid for, there was a wide extension of university foundations, including those of Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield and Bristol. The Board of Agriculture was formed in 1889 and ten years later the Board of Education followed. Nobody had dreamed of controlling horse transport, but the arrival of the motor car led quickly to a national registration scheme. Between 1891 and 1911 the number of persons in government employment, 'civil servants', doubled. In his English History, 1914-1945, AJ.R Taylor wrote: 'Until August 1914 a sensible, law-abiding Englishman could pass through life and hardly notice the existence of the state, beyond the post office and the policeman.' Nevertheless, before the turn of the century many were deploring the extent of government involvement with everyday life.

THE BIRTH OF LABOUR AND

THE WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT

At much the same time, ignored or opposed by most, though not all, of the supporters of democracy and workers' rights, the campaign for women's suffrage, which had existed in a small way for twenty years or more, began to take the form of an organised and widely supported movement. Seventy-three members of parliament had supported John Stuart Mill's attempt to secure votes for women in 1867, but since then the cause had gone into abeyance. A new generation of university-educated women, brought up to discuss all manner of new ideas, was chafing against the refusal of the legal and medical professions to admit them, and their exclusion from public life seemed more and more intolerable. Local women's suffrage groups and societies were formed, but no political party or movement took on their cause. Some of the most vocal opponents were women in leading society positions.

Neither of these developments seemed of great importance to the leaders of political and social life in the 1890s. The great issues were in foreign policy: the rise of imperial Germany, the division of Africa, the South African question; and in trade, where the Conservatives were beginning to promote imperial preference and tariff reform against the old-standing Liberal doctrine of free trade. Public opinion followed their priorities. The period from 1895 to the end of the century, under Salisbury's Conservative-Liberal Unionist government, marked the high point of British imperialism. The occasions of Queen Victoria's golden jubilee in 1887 and diamond jubilee ten years later were made national celebrations, with great pomp and ceremony.

English amateurism, which went arm-in-arm with voluntarism, was an elusive and complex aspect of life. Nobody wanted the railways to be operated by amateur signalmen, or to be chloroformed by an amateur anaesthetist. Nor were such things likely – professional standards were set and maintained across the range of responsible activities. Since 1854, candidates for most government service (though not the 'diplomatic') were appointed on merit after competitive examination. Competitiveness ran quite deep in all sorts of ways, whether in horse racing, or in municipalities vying to build a more sumptuous town hall, or in railway companies building new and uneconomic lines merely to prevent a rival from gaining a little extra traffic. Some unease was detectable around the end of the nineteenth century – a feeling that behind the brilliant façade of the 'top nation' all was not well. 'It is beginning to be hinted that we are a nation of amateurs,' said Lord Rosebery, a former Liberal prime minister, to a student audience in 1900, while the Boer War was going badly. Though England had pioneered the utilization of electricity with Michael Faraday, it was in the United States that electric lighting had been invented, and in Germany that the electric locomotive had first appeared. The cutting edge of industrial progress was no longer to be found in England. In 1902 Albert Einstein began publishing the papers on physics which would overturn the Newtonian concept of the universe. That the rest of the industrialized world should catch up with England was inevitable, but England did not seem to be keeping pace. The decades of the nineteenth century had fostered an English yen for a kind of effortless superiority, which deplored trying too hard, or struggling to succeed.

The schools, particularly the public schools, whose number and influence grew greatly in the later nineteenth century, were the nursery of this viewpoint, but they themselves reflected the expectations and attitudes of the wealthy parents who sent their sons (and eventually their daughters) away to be educated. The education was a largely classical one, based on Greek, Latin and history, with few concessions to the sciences. At its best it turned out able scholars and administrators, imbued with humane values, and a sense of team spirit. But it was an education for future judges, clergymen and administrators, not for scientists or engineers. A manufacturing background, and even more a manufacturing future, had little social prestige.

THE NEW MONEY-MAKERS

As the wealth resulting from mining, quarrying, manufacturing, exporting and importing increased, there was an increasingly wide appreciation of the fact that - quite apart from making things – money in large amounts could be made to generate even more money. London had always been a centre of trade, and this was not a new discovery. Financial houses like that of the Baring family, founded in 1762, played a vital part in supporting international trade and overseas investment. The stock exchange, the merchant banks, the other commodity exchanges that grew up, all were more congenial places than the factory floor, where social life could play a part. The invisible earnings of the City institutions served to compensate for the increasing deficit on materials, goods and products. Despite being the 'workshop of the world', and a major coal exporter up to 1914, the value of Britain's imports had become greater than that of exports, by as much as £134 million in 1911. The country was run by an oligarchy – a government by the few: in this case a combination of the aristocracy with the richest manufacturers and bankers.

But the political power of the oligarchy was based upon the sufferance of the voters. In the first decades of the twentieth century, Britain was not a democracy, in that half the adult population had no vote, but almost half did possess the vote, and were beginning to understand the power which it put in their hands. The most astute member of the 1905 government was David Lloyd George, prominent on the radical and Nonconformist side of the party, and the first Welshman to become a household name in England. His closest ally was Winston Churchill, son of the Tory politician Lord Randolph Churchill.

The constitutional storm was intensified by other political events. From 1903, concern about German ambitions had already brought about alliances with France and Russia. There was a strong popular demand to enlarge the navy, prompted by the German warship building programme.

While the army and navy moved into rehearsed action, it was very quickly plain that far more fighting men were needed. In the course of 1914 recruiting stations were set up and over three million volunteers appeared. There was no invasion threat, but, for the first time since John Paul Jones had fired his cannons off Flamborough Head in 1779, England experienced foreign raids. Ominously for the future, these came from the air, as zeppelin airships, and, later, aircraft attacked Scarborough and other coastal towns.

As had not happened since the early years of the nineteenth century, the country's producing and manufacturing capacity was pushed towards its maximum potential. But the Britain of 1914 had three times the population of 1814 and a vastly greater range of industry. Little of this industry had been geared towards war production, however. The government faced three major and immediate tasks. There was the actual direction of the war.

THE CONDUCT OF THE WAR

Where the government was least successful was in the first of its tasks – managing the actual business of waging war. The dedication and courage of what was at first a largely volunteer army was never in question. But the story of the conduct of strategy is a tragic catalogue of incompetence, indecision, personal animosities and staff infighting. But the British were no worse in these respects than their French allies or their German opponents. Generals trained in colonial wars found themselves controlling a battle-front hundreds of miles long, in a bloody stalemate that lasted four years and in which any attack was fated to gain only a mile or two of ground at the cost of tens of thousands of lives. The western front was too vast and its fate too crucial to be left to the generals; its military and logistical aspects too complex to be influenced by the politicians. Military disasters caused increasing criticism of Asquith's Liberal government, which had been in power on the declaration of war. In May 1915 he made a coalition with the Conservatives, but continuing military failures, the lack of munitions, and a sense that Asquith was not pursuing the war with enough ardour and determination, led to political crisis. The year 1916 saw the battle of Jutland, in which the Grand Fleet succeeded in driving the German High Seas Fleet permanently back into port, but, rather than achieving a Nelson-style annihilation, itself suffered more losses than the enemy. And, by the end of 1916, German submarines were sinking 300,000 tons of British shipping every month.

1916 was the year in which volunteering dried up and – despite the reservations or opposition of many Liberal and Labour politicians – compulsory conscription for men into the armed forces was introduced. The maximum age was forty-one, later increased to fifty.

In 1917, with no progress on the western front, German submarines were winning a sea war, sinking British ships at a terrifying rate, over 600,000 tons in April alone. Convoys, the obvious means, were discounted because 'merchant captains could not keep station'. With the success of the convoy system, and the American entry into the war on the Allied side, it was possible to foresee victory, even though Russia, in the throes of revolution, made a separate peace with Germany, releasing battle-hardened divisions to the western front.

A NATION OF CONSUMERS

In such a country as England, instant large-scale social change is rare. Not suddenly in a rush, but quite stealthily, and by the 1920s quite definitely, the English people had become consumers. The political party which best understood this process was the Conservative Party, which with its protectionist and tariff reform views had won the support of much of industry and business. In the new democracy, it also needed wide popular support, and this came from the section of the community best able to exercise its consuming choice, and keen to extend the range of its possessions, from radios to motor cars, the professional middle class. Its policies made it the natural ally of the farmers, and many farm and rural workers voted with their employers in the interest of their industry, rather than taking the same political side as urban workers. Despite the writings of political philosophers on both sides, the Labour-Tory divide which would typify twentieth-century politics arose from these two concepts: choice plus the ability to choose; and central management by the state. Both could bring social and economic progress and many people saw the way forward as a combination of the two.

THE FAILURE OF APPEASEMENT

Winston Churchill in the 1930s was a supporter of forlorn causes. His reading of the threat to Europe from Nazi Germany was correct, but British politicians, temperamentally opposed to war, were prepared to go to great lengths to avoid it. In the course of 1938 events began to shake both the government itself and the popular approval in which it had basked. A practical politician, of a far from Gladstonian outlook, Chamberlain described the German invasion of Czechoslovakia as 'a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing’. Public opinion pushed the government into a corner; when Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, delaying tactics were no longer possible. After two days of hesitation, war was declared on 3 September.

WORLD WAR II

On 17 September Hitler suspended invasion plans. But though the island was not invaded, it was not inviolate. From August 1940 both Britain and Germany began the night-time bombing of cities and towns. The 'Blitz' on London and other large industrial cities and seaports went on intensively until May 1941. Coventry, Birmingham, Plymouth and Southampton were among those which suffered most. It resulted in the deaths of around 30,000 people and damage or destruction of more than three and a half million houses. The House of Commons was destroyed. Buckingham Palace was hit. Throughout the war the king and his family set a sterling and greatly admired example – they did not leave their home, were reputed to 'eat spam off a gold plate', and a line was painted on the baths to limit the use of hot water.

The German hope that bombing of civilian targets would reduce morale was not borne out. Half-wrecked shops took pride in putting up a 'Business as Usual' notice, and the inconveniences, the 'blackout', shortages, cancelled trains, power cuts, queues, sleeping in underground stations and in damp, chilly air raid shelters, were borne with a grumbling stoicism. 'England can take it' was the consistent message.

State interference in most aspects of life was even more extensive than it had been in 1914-18. Regional government, of a type very different to that late r proposed in 2002, operated efficiently, with regional controllers who had authority to co-ordinate the work of regional offices of the various ministries.

One by-product of the war effort was an improvement in the health and nourishment of the nation's children. School meals were provided, as were cheap milk, vitamin supplements and cod liver oil. Urban slum diseases like rickets were virtually eliminated. Most government thinking about post-war reconstruction was vague, but an exception was the report on the Future of Social Insurance and Allied Services, produced by Sir William Beveridge. This was the most important document on civilian life to be produced in the twentieth century. With wide experience of social administration, economics and politics, Beveridge stretched his brief to the utmost to provide what was in effect the blueprint of the post-war 'welfare state'. His report, published in 1942, envisaged the slaying of the five giants of 'want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness' through a cradle-to-grave social system encompassing free health care, family allowances, unemployment benefit at a decent subsistence level, universal secondary education, and th