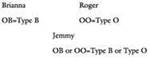

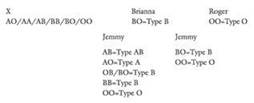

Bree is type B, but Im type A. That means shell have a gene for B and my gene for O, either of which she might have given Jemmy. You could only have given him a gene for type O, because thats all you have.

I nodded at a small rack of tubes near the window, the serum in them glowing brownish-gold in the late afternoon sun.

So. If Bree gave him an O gene, and youhis fathergave him an O gene, hed show up as type Ohis blood wont have any antibodies, and wont react with serum from my blood or from Jamies or Brees. If Bree gave him her B gene, and you gave him an O, hed show up as type Bhis blood would react with my serum, but not Brees. In either case, you might be the fatherbut so might anyone with type-O blood. IF, however

I took a deep breath, and picked up the pencil from the spot where Roger had laid it down. I drew slowly as I talked, illustrating the possibilities.

But I tapped the pencil on the paperif Jemmy were to show as type A or type ABthen his father was not homozygous for type Ohomozygous means both genes are the sameand you are. I wrote in the alternatives, to the left of my previous entry.

I saw Rogers eyes flick toward that X, and wondered what had made me write it that way. It wasnt as though the contender for Jemmys paternity could be just anyone, after all. Still, I could not bring myself to write Bonnetperhaps it was simple superstition; perhaps just a desire to keep the thought of the man at a safe distance.

Bear in mind, I said, a little apologetically, that type O is very common, in the population at large.

Roger grunted, and sat regarding the chart, eyes hooded in thought.

So, he said at last. If hes type O or type B, he may be mine, but not for sure. If hes type A or type AB, hes not minefor sure.

One finger rubbed slowly back and forth over the fresh bandage on his hand.

Its a very crude test, I said, swallowing. I cantI mean, theres always the possibility of a mistake in the test itself.

He nodded, not looking up.

You told Bree this? he asked softly.

Of course. She said she doesnt want to knowbut that if you did, I was to make the test.

I saw him swallow, once, and his hand lifted momentarily to the scar across his throat. His eyes were fixed on the scrubbed planks of the floor, hardly blinking.

I turned away, to give him a moments privacy, and bent over the microscope. I would have to make a grid, I thoughta counting grid that I could lay across a slide, to help me estimate the relative density of the Plasmodium -infected cells. For the moment, though, a crude eyeball count would have to do.

It occurred to me that now that I had a workable stain, I ought to test the blood of others on the Ridgethose in the household, for starters. Mosquitoes were much rarer in the mountains than near the coast, but there were still plenty, and while Lizzie might be well herself, she was still a sink of potential infection.

... four, five, six... I was counting infected cells under my breath, trying to ignore both Roger on his stool behind me, and the sudden memory that had popped up, unbidden, when I told him Briannas blood type.

|

|

|

She had had her tonsils removed at the age of seven. I still recalled the sight of the doctor, frowning at the chart he heldthe chart that listed her blood type, and those of both her parents. Frank had been type A, like me. And two type-A parents could not, under any circumstances, produce a type B child.

The doctor had looked up, glancing from me to Frank and back, his face twisted with embarrassmentand his eyes filled with a kind of cold speculation as he looked at me. I might as well have worn a scarlet A embroidered on my bosom, I thoughtor in this case, a scarlet B.

Frank, bless him, had seen the look, and said easily, My wife was a widow; I adopted Bree as a baby. The doctors face had thawed at once into apologetic reassurance, and Frank had gripped my hand, hard, behind the folds of my skirt. My hand tightened in remembered acknowledgment, squeezing backand the slide tilted suddenly, leaving me staring into blank and blurry glass.

There was a sound behind me, as Roger stood up. I turned round, and he smiled at me, eyes dark and soft as moss.

The blood doesnt matter, he said quietly. Hes my son.

Yes, I said, and my own throat felt tight. I know.

A loud crack broke the momentary silence, and I looked down, startled. A puff of turkey-feathers drifted past my foot, and Adso, discovered in the act, rushed out of the surgery, the huge fan of a severed wing-joint clutched in his mouth.

You bloody cat! I said.

CLEVER LAD

A COLD WIND BLEW from the east tonight; Roger could hear the steady whine of it past the mud-chinked wall near his head, and the lash and creak of the wind-tossed trees beyond the house. A sudden gust struck the oiled hide tacked over the window; it bellied in with a crack! and popped loose at one side, the whooshing draft sending papers scudding off the table and bending the candle flame sideways at an alarming angle.

Roger moved the candle hastily out of harms way, and pressed the hide flat with the palm of his hand, glancing over his shoulder to see if his wife and son had been awakened by the noise. A kitchen-rag stirred on its nail by the hearth, and the skin of his bodhran thrummed faintly as the draft passed by. A sudden tongue of fire sprang up from the banked hearth, and he saw Brianna stir as the cold air brushed her cheek.

She merely snuggled deeper into the quilts, though, a few loose red hairs glimmering as they lifted in the draft. The trundle where Jemmy now slept was sheltered by the big bed; there was no sound from that corner of the room.

Roger let out the breath he had been holding, and rummaged briefly in the horn dish that held bits of useful rubbish, coming up with a spare tack. He hammered it home with the heel of his hand, muffling the draft to a small, cold seep, then bent to retrieve his fallen papers.

O will ye let Telfers kye gae back?

Or will ye do aught for regard o me?

He repeated the words in his mind as he wiped the half-dried ink from his quill, hearing the words in Kimmie Clellans cracked old voice.

It was a song called Jamie Telfer of the Fair Dodheadone of the ancient reiving ballads that went on for dozens of verses, and had dozens of regional variations, all involving the attempts of Telfer, a Borderer, to revenge an attack upon his home by calling upon the help of friends and kin. Roger knew three of the variations, but Clellan had had anotherwith a completely new subplot involving Telfers cousin Willie.

|

|

|

Or by the faith of my body, quo Willie Scott.

Ise ware my dames calfskin on thee!

Kimmie sang to pass the time of an evening by himself, he had told Roger, or to entertain the hosts whose fire he shared. He remembered all the songs of his Scottish youth, and was pleased to sing them as many times as anyone cared to listen, so long as his throat was kept wet enough to float a tune.

The rest of the company at the big house had enjoyed two or three renditions of Clellans repertoire, began to yawn and blink through the fourth, and finally had mumbled excuses and staggered glazen-eyed off to bed en masse leaving Roger to ply the old man with more whisky and urge him to another repetition, until the words were safely committed to memory.

Memory was a chancy thing, though, subject to random losses and unconscious conjectures that took the place of fact. Much safer to commit important things to paper.

I winna let the kye gae back,

Neither for thy love, nor yet thy fear...

The quill scratched gently, capturing the words one by one, pinned like fireflies to the page. It was very late, and Rogers muscles were cramped with chill and long sitting, but he was determined to get all the new verses down, while they were fresh in his mind. Clellan might go off in the morning to be eaten by a bear or killed by falling rocks, but Telfers cousin Willie would live on.

But I will drive Jamie Telfers kye,

In spite of every Scot thats...

The candle made a brief sputtering noise as the flame struck a fault in the wick. The light that fell across the paper shook and wavered, and the letters faded abruptly into shadow as the candle flame shrank from a finger of light to a glowing blue dwarf, like the sudden death of a miniature sun.

Roger dropped his quill, and seized the pottery candlestick with a muffled curse. He blew on the wick, puffing gently, in hopes of reviving the flame.

But Willie was stricken owre the head, he murmured to himself, repeating the words between puffs, to keep them fresh. But Willie was stricken owre the head/And through the knapscap the sword has gane/And Harden grat for very rage/When Willie on the grund lay slain... When Willie on the grund lay slain...

A ragged corona of orange rose briefly, feeding on his breath, but then dwindled steadily away despite continued puffing, winking out into a dot of incandescent red that glowed mockingly for a second or two before disappearing altogether, leaving no more than a wisp of white smoke in the half-dark room, and the scent of hot beeswax in his nose.

He repeated the curse, somewhat louder. Brianna stirred in the bed, and he heard the corn shucks squeak as she lifted her head with a noise of groggy inquiry.

Its all right, he said in a hoarse whisper, with an uneasy glance at the trundle in the corner. The candles gone out. Go back to sleep.

But Willie was stricken owre the head...

Ngm. A plop and sigh, as her head struck the goose-down pillow again.

Like clockwork, Jemmys head rose from his own nest of blankets, his nimbus of fiery fluff silhouetted against the hearths dull glow. He made a sound of confused urgency, not quite a cry, and before Roger could stir, Brianna had shot out of bed like a guided missile, snatching the boy from his quilt and fumbling one-handed with his clothing.

Pot! she snapped at Roger, poking blindly backward with one bare foot as she grappled with Jemmys clothes. Find the chamber pot! Just a minute, sweetie, she cooed to Jemmy, in an abrupt change of tone. Wait juuuuust a minute, now...

Impelled to instant obedience by her tone of urgency, Roger dropped to his knees, sweeping an arm in search through the black hole under the bed.

|

|

|

Willie was stricken owre the head... And through the... kneecap? nobskull? Overwhelmed by the situation, some remote bastion of memory clung stubbornly to the song, singing in his inner ear. Only the melody, thoughthe words were fading fast.

Here! He found the earthenware pot, accidentally struck the leg of the bed with itthank Christ, it didnt break!and bowled it across the floor to Bree.

She clapped the now-naked Jemmy down onto it with an exclamation of satisfaction, and Roger was left to grope about in the semi-dark for his fallen candle while she murmured encouragements.

OK, sweetie, yes, thats right...

Willie was struck about... no, stricken...

He found the candle, luckily uncracked, and sidled carefully round the drama in progress to kneel and relight the charred wick from the embers of the fire. While he was at it, he poked up the embers and added a fresh stick of wood. The fire revived, illuminating Jemmy, who was making what looked like a very successful effort to go back to sleep, in spite of his position and his mothers urging.

Dont you need to go potty? she was saying, shaking his shoulder gently.

Go potty? Roger said, this curious locution pushing the remnants of the verse from his mind. What do you mean, go potty? It was his personal opinion, based on current experience as a father, that small children were born potty, and improved very slowly thereafter. He said as much, causing Brianna to give him a remarkably dirty look.

What? she said, in an edgy tone. What do you mean, theyre born potty? She had one hand on Jemmys shoulder, balancing him, while the other cupped his round little belly, an index finger disappearing into the shadows below to direct his aim.

Potty, Roger explained, with a brief circular gesture at his temple in illustration. You know, barmy. Daft.

She opened her mouth to say something in reply to this, but Jemmy swayed alarmingly, his head sagging forward.

No, no! she said, taking a fresh grip. Wake up, honey! Wake up and go potty!

The insidious term had somehow taken up residence in Rogers mind, and was merrily replacing half the fading words of the verse he had been trying to recapture.

Willie sat upon his pot/The sword to potty gane...

He shook his head, as though to dislodge it, but it was too latethe real words had fled. Resigned, he gave it up as a bad job and crouched down next to Brianna to help.

Wake up, chum. Theres work to be done. He drew a finger gently under Jemmys chin, then blew in his ear, ruffling the silky red tendrils that clung to the childs temple, still damp with sleep-sweat.

Jemmys eyelids cracked in a slit-eyed glower. He looked like a small pink mole, cruelly excavated from its cozy burrow and peering balefully at an inhospitable upper world.

Brianna yawned widely, and shook her head, blinking and scowling in the candlelight.

Well, if you dont like go potty, what do you say in Scotland, then? she demanded crabbily.

Roger moved the tickling finger to Jems navel.

Ah... I seem to recall a friend asking his wee son if he needed to do a poo, he offered. Brianna made a rude noise, but Jemmys eyelids flickered.

Poo, he said dreamily, liking the sound.

Right, thats the idea, Roger said encouragingly. His finger twiddled gently in the slight depression, and Jemmy gave the ghost of a giggle, beginning to wake up.

Pooooooo, he said. Poopoo.

Whatever works, Brianna said, still cross, but resigned. Go potty, go poojust get it over with, all right? Mummy wants to go to sleep.

Perhaps you should take your finger off of his... mmphm? Roger nodded toward the object in question. Youll give the poor lad a complex or something.

|

|

|

Fine. Bree took her hand away with alacrity, and the stubby object sprang back up, pointing directly at Roger over the rim of the pot.

Hey! Now, just a minhe began, and got his hand up as a shield just in time.

Poo, Jemmy said, beaming in drowsy pleasure.

Shit!

Chit! Jemmy echoed obligingly.

Well, thats not quitewould you stop laughing? Roger said testily, wiping his hand gingerly on a kitchen rag.

Brianna snorted and gurgled, shaking her head so the straggling locks of hair that had escaped her plait fell down around her face.

Good boy, Jemmy! she managed.

Thus encouraged, Jemmy took on an air of inner absorption, scrunched his chin down into his chest, and without further ado, proceeded to Act Two of the evenings drama.

Clever lad! Roger said sincerely.

Brianna glanced at him, momentary surprise interrupting her own applause.

He was surprised himself. He had spoken by reflex, and hearing the words, just for a moment, his voice hadnt sounded like his own. Very familiarbut not his own. It was like writing the words of Clellans song, hearing the old mans voice, even as his own lips formed the words.

Aye, thats clever, he said, more softly, and patted the little boy gently on his silky head.

He took the pot outside to empty it while Brianna put Jemmy back to bed with kisses and murmurs of admiration. Basic sanitation accomplished, he went to the well to wash his hands before coming back inside to bed.

Are you through working? Bree asked drowsily, as he slid into bed beside her. She rolled over and thrust her bottom unceremoniously into his stomach, which he took as a gesture of affection, given the fact that she was about thirty degrees warmer than he was after the sortie outside.

Aye, for tonight. He put his arms round her and kissed the back of her ear, the warmth of her body a comfort and delight. She took his chilly hand in hers without comment, folded it, and tucked it snugly beneath her chin, with a small kiss on the knuckle. He stretched slightly, then relaxed, letting his muscles go slack and feeling the tiny movements as their bodies adjusted, shaping to each other. A faint buzzing snore rose from the trundle, where Jemmy slept the sleep of the righteously dry.

Brianna had freshly smoored the fire; it burned with a low, even heat and the sweet scent of hickory, making small occasional pops as the buried flame reached a pocket of resin or a spot of damp. Warmth crept over him, and sleep tiptoed in its wake, drawing a blanket of drowsiness up round his ears, unlocking the tidy cupboards of his mind, and letting all the thoughts and impressions of the day spill out in brightly colored heaps.

Resisting unconsciousness for a last few moments, he poked desultorily among the scattered riches thus revealed, in the faint hope of finding a corner of the Telfer song poking out; some scrap of word or music that would allow him to seize the vanished verses and drag them back into the light of consciousness. It wasnt the story of the ill-fated Willie that emerged from the rubble, though, but rather a voice. Not his own, and not that of old Kimmie Clellan, either.

Clever lad! it said, in a clear warm contralto, tinged with laughter. Roger jerked.

Whaju say? Brianna mumbled, disturbed by the movement.

Go onbe clever, he said slowly, echoing the words as they formed in his memory. Thats what she said.

Who? Brianna turned her head, with a rustle of hair on the pillow.

My mother. He put his free hand round her waist, resettling them both. You asked what they said in Scotland. Id forgotten, but thats what she used to say to me. Go onbe clever! or Do ye need to be clever?

Bree gave a small grunt of sleepy amusement.

Well, its better than poo, she said.

They lay quiet for a bit. Then she said, still speaking softly, but with all traces of sleep gone from her voice, You talk about your dad now and thenbut Ive never heard you mention your mother before.

He gave a one-shouldered shrug, bringing his knees up against the yielding backs of her thighs.

I dont remember a lot about her.

How old were you when she died? Briannas hand floated up to rest over his.

Oh, four, I think, nearly five.

Mmm. She made a small sound of sympathy, and squeezed his hand. She was quiet for a moment, alone in private thought, but he heard her swallow audibly, and felt the slight tension in her shoulders.

What?

Oh... nothing.

Aye? He disengaged his hand, used it to lift the heavy plait aside, and gently massaged the nape of her neck. She turned her head away to make it easier, burying her face in the pillow.

|

|

|

JustI was just thinkingif I died now, Jemmys so younghe wouldnt remember me at all, she whispered, words half-muffled.

Yes, he would. He spoke in automatic contradiction, wanting to give her reassurance, even knowing that she was likely right.

You dont remember, and you were lots older when you lost your mother.

Oh... I do remember her, he said slowly, digging the ball of his thumb into the place where her neck joined her shoulder. Only, its just in bits and pieces. Sometimes, when Im dreaming, or thinking of something else, I get a quick glimpse of her, or some echo of her voice. A few things I recall clearlylike the locket she used to wear round her neck, with her initials on it in wee red stones. Garnets, they were.

That locket had perhaps saved his life, during his first ill-fated attempt to pass through the stones. He felt the loss of it now and then, like a small thorn buried beneath the surface of the skin, but pushed the feeling aside, telling himself that after all, it was nothing more than a bit of metal.

At the same time, he missed it.

Thats a thing, Roger. Her voice held a hint of sharpness. Do you remember her? I meanwhat would Jemmy know about meabout you, for that matterif all he had left of us wasshe cast about for some suitable objectwas your bodhran and my pocket knife?

Hed know his dad was musical, and his mum was bloodthirsty, Roger said dryly. Ouch! He recoiled slightly as her fist came down on his thigh, then set his hands placatingly on her shoulders. No, really. Hed know a lot about us, and not just from the bits and bobs wed left behind, though those would help.

How?

Well... Her shoulders had relaxed again; he could feel the slender edge of her shoulder blade, hard against the skinshe was too thin, he thought. You studied history for a time, didnt you? You know how much one can tell from homely objects like dishes and toys.

Mmm. She sounded dubious, but he thought that she simply wanted to be convinced.

And Jem would know a lot more than that about you, from your drawings, he pointed out. And a hell of a lot more than a son ought, if he ever read your dream-book, he thought. The sudden impulse to say so, to confess that he himself had read it, trembled on his tongue, but he swallowed it. Beyond simple fear of how she might respond if she discovered his intrusion, was the greater fear that she would cease to write in it, and those small secret glimpses of her mind would be lost to him.

I guess thats true, she said slowly. I wonder if Jem will drawor be musical.

If Stephen Bonnet plays the flute, Roger thought cynically, but choked off that subversive notion, refusing to contemplate it.

Thats how hell know the most of us, he said instead, resuming his gentle kneading. Hell look at himself, aye?

Mmm?

Well, look at you, he pointed out. Everyone who sees you says, You must be Jamie Frasers lass! And the red hair isnt the only thingwhat about the shooting? And the way you and your mother are about tomatoes...

She smacked her lips reflexively, and giggled when he laughed.

Yeah, all right, I see, she said. Mmm. Why did you have to mention tomatoes? I used the last of the dried ones last week, and itll be six months before theyre on again.

Sorry, he said, and kissed the back of her neck in apology.

I did wonder, he said, a moment later. When you found out about Jamiewhen we began to look for himyou must have wondered what he was like. He knew she had; he certainly had. When you found himhow did he compare? Was he at all like you thought hed be, from what you knew about him already? Orfrom what you knew about yourself?

That made her laugh again, a little wryly.

I dont know, she said. I didnt know then, and I still dont know.

What dye mean by that?

Well, when you hear things about somebody before you meet them, of course the real person isnt just like what you heard, or what you imagined. But you dont forget what you imagined, either; that stays in your mind, and sort of merges with what you find out when you meet them. And then She bent her head forward, thinking. Even if you know somebody first, and then hear things about them laterthat kind of affects how you see them, doesnt it?

Aye? Mmm, I suppose so. Do ye mean... your other dad? Frank?

I suppose I do. She shifted under his hands, shrugging it away. She didnt want to talk about Frank Randall, not just now.

What about your parents, Roger? Do you figure thats why the Reverend saved all their old stuff in those boxes? So later you could look through it, learn more about them, and sort of add that to your real memories of them?

Iyes, I suppose so, he said uncertainly. Not that I have any memories of my real dad in any case; he only saw me the once, and I was less than a year old then.

But you do remember your mother, dont you? At least a little bit?

She sounded slightly anxious; she wanted him to remember. He hesitated, and a thought struck him with a small shock. The truth of it was, he realized, that he never consciously tried to remember his mother. The realization gave him a sudden and unaccustomed feeling of shame.

She died in the War, didnt she? Brees hand had taken up his suspended massage, reaching back to gently knead the tightened muscle of his thigh.

Yes. Shein the Blitz. A bomb.

In Scotland? But I thought

No. In London.

He didnt want to speak of it. He never had spoken of it. On the rare occasions when memory led in that direction, he veered away. That territory lay behind a closed door, with a large No Entry sign that he had never sought to pass. And yet tonight... he felt the echo of Brees brief anguish at the thought that her son might not recall her. And he felt the same echo, like a faint voice calling, from the woman locked behind that door in his mind. But was it locked, after all?

With a hollow feeling behind his breastbone that might have been dread, he reached out and put his hand on the knob of that closed door. How much did he recall?

My Gran, my mothers mum, was English, he said slowly. A widow. We went south to live with her in London, when my dad was killed.

He had not thought of Gran, any more than his mum, in years. But with his speaking, he could smell the rosewater and glycerine lotion his grandmother had used on her hands, the faintly musty smell of her upstairs flat in Tottenham Court Road, crammed with horsehair furniture too large for it, remnants of a previous life that had held a house, a husband, and children.

He took a deep breath. Bree felt it, and pressed her broad firm back encouragingly against his chest. He kissed the back of her neck. So the door did openjust a crack, maybe, but the light of a wintry London afternoon shone through it, lighting up a stack of battered wooden blocks on a threadbare carpet. A womans hand was building a tower with them, the faint sun scattering rainbows from a diamond on her hand. His own fingers curled in reflex, seeing that slim hand.

Mummy mothershe was small, like Gran. That is, they both seemed big, to me, but I remember... I remember seeing her stand on her tiptoes to reach things down from the shelf.

Things. The tea-caddy, with its cut-glass sugar bowl. The battered kettle, three mismatched mugs. His had had a panda bear on it. A package of biscuitsbright red, with a picture of a parrot... My God, he hadnt seen those kind ever againdid they still make them? No, of course not, not now...

He pulled his veering mind firmly back from such distractions.

I know what she looked like, but mostly from pictures, not from my own memories. And yet he did have memories, he realized, with a disturbing sensation in the pit of his stomach. He thought Mum, and suddenly he didnt see the photos anymore; he saw the chain of her spectacles, a string of tiny metal beads against the soft curve of a breast, and a pleasant warm smoothness, smelling of soap against his cheek; the cotton fabric of a flowered housedress. Blue flowers. Shaped like trumpets, with curling vines; he could see them clearly.

What did she look like? Do you look like her at all?

He shrugged, and Bree shifted, rolling over to face him, her head propped upon her outstretched arm. Her eyes shone in the half-dark, sleepiness overcome by interest.

A little, he said slowly. Her hair was dark, like mine. Shiny, curly. Lifting in the wind, sprinkled with white grains of sand. Hed sprinkled sand on her head, and she brushed it from her hair, laughing. A beach somewhere?

The Reverend kept some pictures of her, in his study. One showed her holding me on her lap. I dont know what we were looking atbut both of us look as though were trying hard to keep from laughing. We look a lot alike in that one. I have her mouth, I thinkand... maybe... the shape of her brows.

For a long time he had felt a tightness in his chest whenever he saw the pictures of his mother. But then it had passed, the pictures lost their meaning and became no more than objects in the casual clutter of the Reverends house. Now he saw them clearly once again, and the tightness in his chest was back. He cleared his throat hard, hoping to ease it.

Need water? She made to rise, reaching for the jug and cup she kept for him on the stool by the bed, but he shook his head, a hand on her shoulder to stop her.